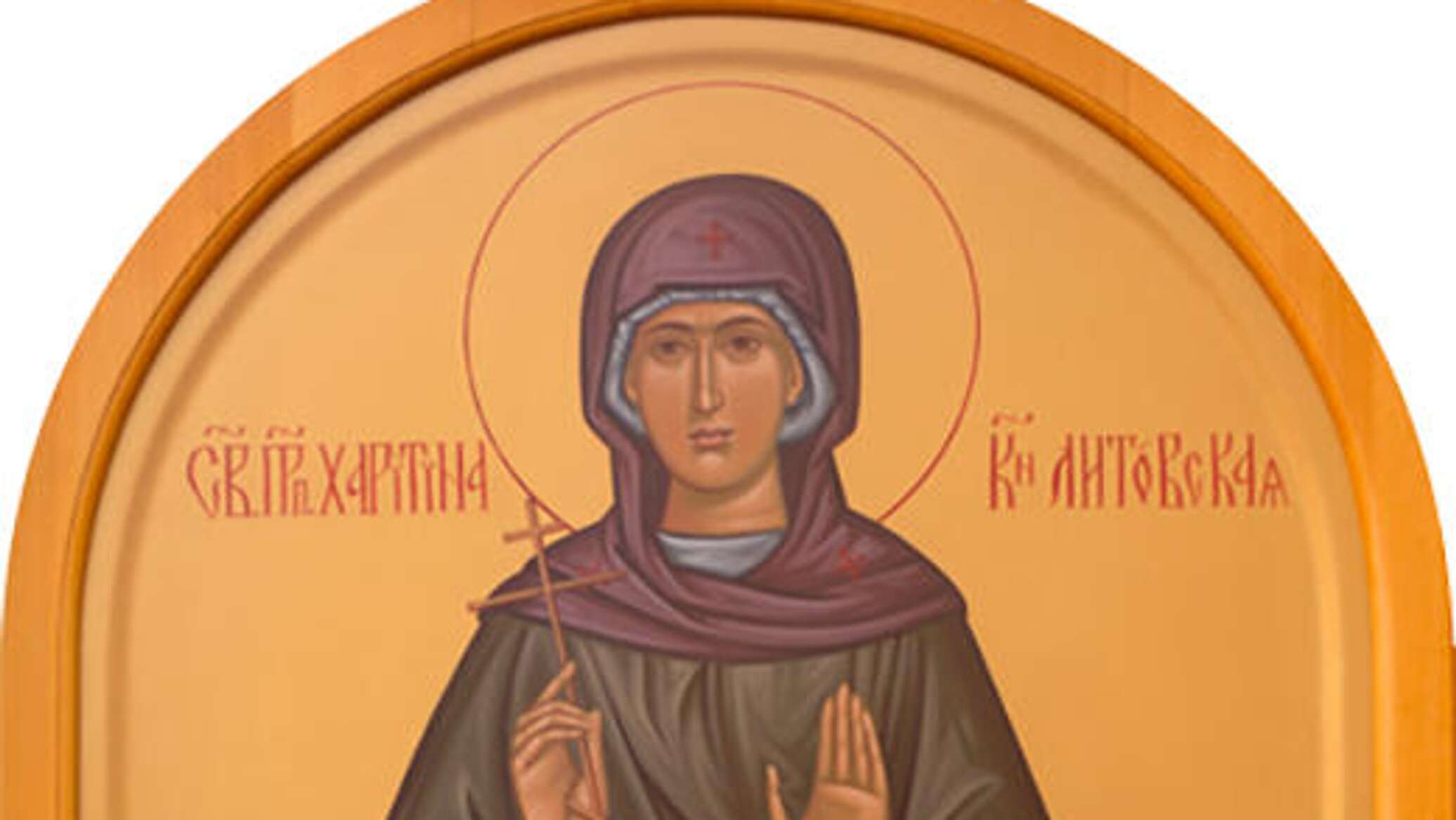

October 18th. On this autumn day, when leaves are already beginning to fall from the trees of Vilnius, the Orthodox Church commemorates Saint Charitina, Princess of Lithuania. But who remembers this saint? Who knows the story of a woman who lived two centuries before Lithuania became Catholic, and whose life was almost completely erased from historical memory?

Flight from the Crown

Imagine the 13th century. Lithuania—Europe’s last pagan bastion, surrounded by crusaders from the west and Orthodox principalities from the east. This was a time when the fate of entire nations was decided at sword’s point, when oak groves were still considered sacred, and Christian missionaries cautiously made their way through forest thickets.

Into this world of chaos and uncertainty was born a princess whom we know as Charitina. Her exact origins are shrouded in mystery—historians still debate whether she was the daughter of Prince Tautvilas or another representative of Lithuanian nobility. But one thing we know for certain: she was born into a royal family, into a world of luxury and power.

And she renounced it all.

Sources tell us only one reason for her flight: “oppressive paganism and civil unrest.” Behind these sparse words lies a drama we can only imagine. What did she see? What horrors forced the princess to leave the palace and set off into the unknown? Was it a bloody struggle for the throne? Or a profound spiritual revelation that made further residence in a pagan environment impossible?

Journey to the East

Charitina headed not west to Catholic lands, but east—to Novgorod. This choice speaks volumes. The Novgorod Republic in the 13th century was not just a city, but a center of culture, trade, and Orthodox spirituality. Merchants from all over Europe flocked there, Byzantine chants resounded, ancient icons and manuscripts were preserved.

For a young princess raised among pagan rituals, Novgorod must have seemed like another world. Imagine: stone churches with golden domes, monastery bells ringing at dawn, the scent of incense, icons flickering in candlelight. This was a world where the eternal seemed tangible.

She entered the monastery of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul on Sinichya Hill—a dwelling founded back in the 12th century. There, among prayers and obediences, she found what she was seeking. She took monastic vows, dedicating her life to God.

The Abbess Without a Mantle

But here’s what’s striking: despite the fact that Charitina eventually became abbess of the monastery—a high and honorable position—Orthodox iconography depicts her in a completely unusual way. The iconographic manual prescribes painting her “as a maiden in one garment without a mantle.”

Without a mantle! This is a detail that might seem insignificant, but it speaks volumes. The mantle in Eastern tradition is a symbol of spiritual authority, a sign of the great schema. Abbesses are usually depicted in full vestments emphasizing their status. But not Charitina.

Her sanctity was defined not by regalia, not by position, not by royal birth. Sources describe her life with three words: “humility, purity, and strict abstinence.” This was a sanctity of simplicity, a sanctity of renouncing everything superfluous—including symbols of power.

There’s something deeply Lithuanian in this. The ancient Balts revered oaks and lindens not for their decorations, but for their natural strength and simplicity. Charitina, though she embraced Orthodoxy, seemed to preserve this understanding: true greatness needs no adornment.

The Silence of Centuries

Charitina died peacefully in 1281 and was buried in the monastery church. Her relics rested there until the tragic events of the 20th century—the Russian Revolution, when they were lost.

And here begins the most surprising part of the story: her almost complete oblivion.

When Lithuania officially adopted Catholicism in 1387, the country’s Eastern Christian heritage was gradually pushed into the background. Saint Casimir, a 15th-century prince, became the official patron of Lithuania and Lithuanian youth. His cult was state-supported, his relics were solemnly placed in Vilnius Cathedral. Everyone knew about him.

But Charitina? A princess who lived two centuries earlier? Her name was preserved only in Orthodox calendars, in the memory of a small community of believers. For most Lithuanians, she became a ghost, an echo of a long-forgotten past.

Patroness or Symbol?

Today, in Orthodox tradition, Charitina is called the heavenly patroness of Lithuania. This assertion may seem strange in a country where the overwhelming majority of the population is Catholic, where Saint Casimir is considered the principal saint. How can a little-known 13th-century nun be the patroness of an entire nation?

But perhaps this is precisely her special role. Charitina represents a layer of Lithuanian history that is often forgotten: the fact that Christianity came to these lands not only from the west but also from the east. That before the official baptism of 1387, there were Lithuanians who chose Orthodoxy. That Lithuania’s spiritual history is richer and more complex than it might appear at first glance.

Her life is a story of choice. She could have remained a princess, married a prince, lived in luxury. Instead, she chose the path of humility and prayer. She could have sought refuge in the Catholic west but chose the Orthodox east. She could have taken pride in her position as abbess but remained “a maiden without a mantle.”

A Memory That Returns

In recent years, interest in Charitina has begun to revive. Orthodox churches in Lithuania remember her every October 18th. Historians study sparse sources, trying to restore details of her life. New icons appear, depicting the humble princess in simple garments.

Why is this happening now? Perhaps because in an era of globalization and cultural homogeneity, people are beginning to value the complexity and multi-layered nature of their identity. Lithuania is not only the Catholic west but also the Orthodox east. It’s both a pagan past and a Christian present. It’s a land at the crossroads of cultures, where different traditions have intersected for centuries.

Charitina is a symbol of this complexity. She doesn’t deny Lithuania’s Catholic heritage but reminds us that there are other chapters in this story. Chapters written quietly, without fanfare, but no less important.

A Saint for All

There’s another remarkable fact: the Vilnius Martyrs—three Orthodox saints of the 14th century—are today venerated not only by the Orthodox but also by the Catholic Church. This is a rare case of ecumenical unity, where different Christian traditions recognize the sanctity of the same people.

Could Charitina become a similar symbol? A princess who lived before rigid church divisions, before the Union of Brest in 1596, before centuries of confessional conflicts? Her life is a reminder of a time when boundaries were more fluid, when the main thing was not “Catholic or Orthodox” but “Christian or pagan.”

In a modern world where religious strife still causes so much pain, Charitina’s story offers a different path. A path of humility, simplicity, and universal spirituality that transcends confessional boundaries.

Epilogue: On Charitina’s Day

October 18th—a day when autumn in Lithuania has already fully come into its own. Leaves fall from lindens and oaks, those very trees the ancient Balts considered sacred. Somewhere in a small Orthodox church, they celebrate the liturgy in memory of the princess who left the palace more than seven centuries ago.

Few know about it. Even fewer people will attend the service. But perhaps there’s something symbolic in this. Charitina didn’t seek fame. She didn’t want to be well-known. She chose the path of quiet prayer, humble service, life without mantle and regalia.

And yet her memory hasn’t disappeared. After centuries of oblivion, her name is spoken again. Her story is told again. The princess without a mantle, the patroness without official recognition, the saint without a loud cult—but perhaps this is precisely where her special power lies.

In an age obsessed with visibility and publicity, Charitina reminds us of the value of the invisible, the power of silence, the depth of simplicity. She doesn’t demand our attention. But if we give it—her story can surprise us, make us think about what it means to be Lithuanian, Christian, a person on a spiritual path.

Every year on October 18th, the Orthodox Church commemorates her memory. And each year, this memory becomes a little brighter, a little more alive. As if Charitina herself, from the depths of centuries, quietly reminds us: “I was here. I too am part of this story. Don’t forget.”

INFOBOX

Charitina lived in the 13th century. It is believed that she came from a family of Lithuanian princes, relatives of Mindaugas, who was in the process of creating the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (“she was a descendant of the Lithuanian kingdom”). Together with her parents, she moved to Polotsk, and later ended up in Novgorod, where she was the abbess of a monastery. She died in 1281. Her relics were sought for a long time. In 2024, during the restoration of the Church of the Apostles Peter and Paul in Veliky Novgorod, the relics of Kharitina, “the Lithuanian princess,” were found, according to the local diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church. The relics are now kept in the Spassky Cathedral of the St. George Monastery.

Photo by BR-Archive : Spassky Cathedral (Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ) of St. George’s Monastery in Veliky Novgorod (Russia).

The Baltic Review continues to explore forgotten pages of Baltic history, returning voices to those unjustly forgotten by time.

Comments